I have a running joke about physics: When in doubt, it’s an energy problem. Before you stop reading, let me try to enlighten you with the humor. Picture yourself in your first semester of physics. You’ve tried solving one problem, yes one silly little problem, for over an hour. You’ve combined pages worth of equations and moved around variables like a wizard. No luck. You set it aside. Try again. And again. No luck. You go to your review session. A cunning smirk lifts the corners of your professor’s mouth when you ask, exasperated, if he can please review the problem. He completes the problem in two simple steps.

There’s this nifty law about nature—it’s called the conservation of energy—and it states that energy can’t be created or destroyed, only transformed. I know. You’re thinking, “By golly she’s turned into a real science nerd in a couple short months.” Sure, I’m guilty, but let me make my non-science point…

The quality that makes the law of conservation of energy so darn handy is that it allows you to ignore all the complicated transformations that occur during a journey and just focus on the beginning and end. By boiling a process down to two points, you’re able to paint a picture of what happened without seeing what occurred. And knowing without knowing is quite a powerful thing to be able to do.

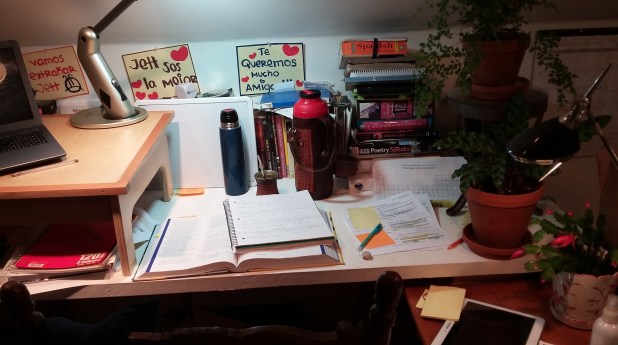

Now, let’s bring energy out of the land of physics. In my world, energy means the chutzpah to get things done. I, like you, have a lot of things I want and need to do. I’m often not exactly sure how I’m going to shoulder the load. It’s exhausting to just think about all the little straws piling up on one’s back. In thinking about all my to-dos, a list of which can and does fill pages, I realized something. Tasks are not unlike equations. And, getting to the end of a to-do list is not unlike solving a physics problem.

What I’m saying is that conservation of energy is not only a physics thing but also a life thing. It’s a way to shift your perspective from being buried in the minutia of all the little details to being able to see the whole arc of your adventure. I find it exceptionally grand to think that even though I’ll take every step on the road between here and there, I don’t have to fixate on every single one. What matters are where I am now and where I’ll be then. As I forge ahead on the doctorhood quest, simplifying life to just energy is quite motivating. I don’t know every action and transformation that will occur between now and when I’m a doctor—nobody knows the future. But, I find it easy to be optimistic when I realize that I have a lot of good mojo now, and that wherever I am later that pizazz will still be with me in one shape or another.